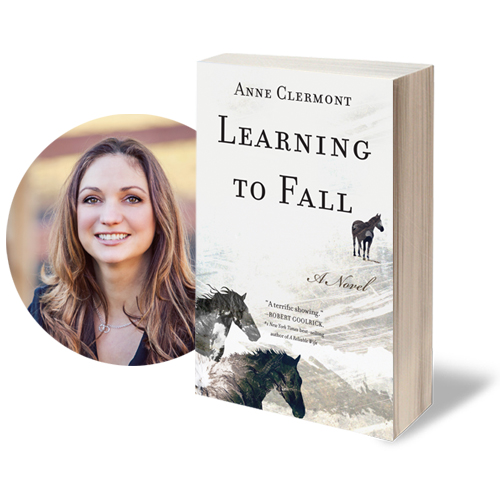

This post is brought to you by SparkPress author Anne Clermont, whose debut contemporary women’s novel Learning to Fall (Aug. 2, 2016) has been called by Redbook “the best equine literary experience since Seabiscuit”, and praised by numerous New York Times #1 bestselling authors, as well as Olympic Equestrian team members and Del Mar Grand Prix winners.

Writing styles are as unique as species of insects found in the Amazon. If you attend any craft panel at a writers’ conference, you’ll come across two main schools of thought: Great fiction is either plot driven or character driven. Editors, agents, and writers will proclaim that one is much more important than the other. (Of course they don’t mention that they favor it based on what type of fiction they like to edit, represent, or read.) In general, many genres, such as mystery and sci-fi, tend to be plot driven. While book club fiction and literary fiction tends to be more character driven.

Realistically, I don’t think you can have a great novel without having both.

Great characters make us care about and empathize with them; they make us feel as though we’re in their world experiencing their lives. If nothing ever happened to move the story forward, though, we’d throw the book across the room and scream in frustration. We need to see conflict. We need plot twists and action to keep us turning pages. There is only so much character development that will keep us up at night. Having said that, the character must grow over the course of the novel—but character development can be tricky. She must see things differently than she did at the beginning of the story . Otherwise, what was the point of going through the hell she just did? Could you get by without having your character change? Of course. Will it be a character that you remember many months (or years) down the line? I doubt it.

Although my women’s contemporary, coming-of-age novel Learning to Fall has several key characters, the book was really about Brynn Seymour’s story. When I first started writing the novel, each character was completely developed . . . though mostly only in my mind. What I quickly learned was that I actually had to show the personality of each character in between the sentences that moved the plot forward. To make Brynn relatable, and her voice likeable enough to have a reader turn 280-ish pages, I had to make sure her character changed, grew, and learned, as the story progressed.

For my main heroine to change and transform into who she was supposed to be in Learning to Fall, here are five things I had to implement.

1) Coming of age

In the opening scenes we are introduced to Brynn and her father, Luke. Very quickly we realize that even though Brynn is in her third year of veterinary school, she reverts to being indecisive and meek while in her father’s presence. We also see this in the early scenes with her mom.

Difficulty in crafting: Finding and conveying Brynn’s voice, mature enough for a woman in her early twenties, yet passive and submissive when with her family and boyfriend.

Change: She becomes a grown woman, capable of finally speaking up for herself and following her own dreams.

2) Forgiveness

After the tragic inciting incident scene, Brynn takes on more responsibility than she’s ever experienced. Not only that, she feels guilty and blames herself for the accident that changes her life. Brynn carries the guilt throughout the novel, but with some help, she moves forward.

Difficulty in crafting: Showing Brynn’s guilt without constantly hammering the reader over the head with it.

Change: Brynn forgives herself.

3) Letting go

A big theme throughout Learning to Fall is letting go. Letting go of expectations, desires, fear, guilt. Letting go of the outcome of the life.

Difficulty in crafting: Weaving in facets of Brynn’s controlling nature.

Change: Brynn finally realizes that to achieve what she wants to do in life, she must let go of what her father expected of her, her mother’s plans for her life, and what her boyfriend wanted from her. She has to become comfortable with both winning and losing.

4) Overcoming fear

While this ties in with ‘letting go’ above, it is also a very real and separate issue for Brynn and her mother.

Difficulty in crafting: Overcoming fear doesn’t mean pounding on your chest and rushing out into the jungle, and oftentimes it is much more subtle. Showing nuanced emotions without being overly obvious and spelling it out for the reader was a real challenge.

Change: Brynn overcomes her fear of failure.

5) The nitty gritty

Outside of the bigger themes in story and character arcs, a writer can sprinkle in details and actions that help lend credibility to each character. For example, Brynn goes from eating junk food and drinking alcohol and coffee to eating healthy, natural foods and drinking herbal tea. This is an external manifestation of the inner changes going on.

Difficulty in crafting: The first few drafts had a lot of ‘everything and the kitchen sink’ tossed in. I did what many first time novelists do: add in every thought and plot twist and character trait that I thought might make the novel better.

Change: In the end I had to cut much of those additions to focus on the fine details. Doing that within a limited number of pages is the real art. After all, most of us aren’t writing a thousand-page tome. It’s like weaving a silk tapestry, pulling all the threads through to create a bigger piece that resonates with the reader.

Helpful post, both for understanding character arc and the challenges faced during character creation. Thanks.