Summer is in full swing, and vacations and downtime abound. You may be working on some writing, traveling—or both. What if you want to combine travel into your story, or set it in a location that you’ve fallen in love with, or maybe haven’t even visited yet?

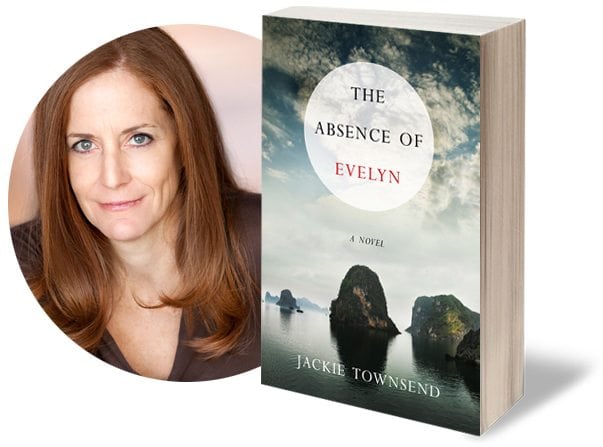

Everyone loves to be swept away to new settings or exotic locations by way of book, and what better time practice that craft than summer? So we tapped into SparkPress author Jackie Townsend on the art of writing a book set in multiple locations around the world—as well as from multiple POVs. Her novel, The Absence of Evelyn, came out in Spring 2017, and has been praised by Redbook, Yahoo!, Bustle, and more.

Foreign countries play like living, breathing characters in my novels, and this quote by Goethe is one of my favorites: “Nothing can be compared to the new life that the discovery of another country provides for a thoughtful person. Although I am still the same I believe to have changed to the bones.”

When I set out to write a novel, I begin with a relationship in conflict. Sisters, a mother and a daughter, lovers, or a married couple. I place those characters in a scene, start writing, and see where the story takes me. Usually somewhere far away. Actually, not usually. Always. Apparently, displacement is part of my psyche.

Whether in search of escape, truth, love, meaning, or redemption, my characters tend to cross seas to find it. To lose oneself in another language, culture, and geography, is to open oneself up to not only great possibility but great vulnerability, and as Goethe said, it is difficult to walk away from that experience unaltered.

What writer doesn’t want their characters to be altered?

Journeys live on long after you’ve returned home. They keep coming back to you. The trains, planes, and automobiles, the scooters, rickshaws, and bicycle taxis. The unrecognizable foods and indecipherable sounds. The sense of isolation and aloneness amongst such beauty and wonder. This is how I want to leave my reader feeling, as if they’ve been transported even though they haven’t left their bedroom. I want the feeling to stay with them long after they’ve put the book down, settling itself inside the grit and grime of their daily lives, for foreignness isn’t just about being overseas, it’s a metaphor for living. Who hasn’t had the sense, when conversing with a spouse or an offspring, that that person is speaking to you in a different language? Isn’t entering a relationship, in fact, like crossing a border into a foreign country? Full of all the exploration and awe, the abyss of unmet expectations? Who can’t relate?

It may be years later before a scene from a journey of mine exhumes itself as if from some buried tomb in my chest and finds its way into my writing. I’ll be surprised to see it there on the page. Invigorated, I’ll hunt down my notes or journals from back then. Those that I will ultimately find useless, for time has reshaped the journey in my mind. What our memories do is change and morph and grow. There are no longer details, time and place, an itinerary—I’m separate from all that now, and this is when my writing tends to be better.

I often forgo applying labels or markers to a location.

I want the reader to feel as lost as I once was, as lost as my character is now. Avoiding tourist sites like the Spanish Steps in Rome, for instance. I’d rather my character stumble upon a darkened piazza left for dead; Piazza Sant’Eustachio, maybe you’ve heard of it, but likely you have not. It doesn’t matter. The idea is to set the mood for the scene, not check off sites from a list of the well-traveled. Readers can buy a guidebook for that.

If my characters go to a famous monument, I might describe it as a giant staircase into heaven, but I won’t say its real name. If you’ve been to Angkor Wat you might recognize the temple I am describing—but what I don’t want to do is have the reader feel as if they’ve been left out of some secret club. I want them to feel as if they’d just entered one.

Same with language. A foreigner in Italy is not going to understand the Italian phrases thrown at them on the street, and so I don’t expect my reader to either. I will often leave a phrase untranslated:

“Bella Roma no?”

“Mamma, ma dai, mamma.”

My character didn’t catch the meaning, so neither should my reader. Or that’s my theory anyway. This doesn’t always work, and I’ve heard from readers on this. I’ve learned there’s a balance.

I am a minimalist writer. Long, languorous paragraphs describing rolling hills and undulating horizons a la Frances Mayes are not my style. “The fog begins to lift, a pink sun overtakes the sky, and the hills grow wavier, a richer green. Clusters of terra cotta emerge on distant hills along with castles and campanili that don’t seem entirely real, until they get closer, and then they still don’t seem real.” I don’t say which castle or campanili, or even the hill town to which I’m ascending via car—“La Morra, Barolo, Verduno, Cherasco, Roddi, Grinzane… Signs point crooked arrows in all directions.”

It’s an art in subtly. I want to create a feeling, a mood for the narrative. I don’t want my readers consulting a map. More important is to have the reader’s every sense heightened. The smell of petrol and rotten fish, jasmine and fermented grapes. Sounds of a sputtering scooter, the haggling of foreign tongues, the tin-like taste of a wine gone sour, air so moist you could cup in your hands and drink it.

Travel is often far from romantic. A trip to Italy is not about narrow cobbled streets, pizza o pasta, or that bello Italian man who is going to sweep you off your feet. Leave off stereotypes, write the truth. About the pigeon you discovered in your shower. Out your hotel room window, a fog thick enough to diffuse your view of the Taj Mahal but not the men squatting on the hill beside it doing their business. The sleep deprivation, the exasperation over getting lost, the arguments, the aching back and legs, all in deference to the road less traveled—however illusive—another hotel, another window, under which a beggar stands, crying into the night.

About The Absence of Evelyn, by Jackie Townsend

About The Absence of Evelyn, by Jackie Townsend

Newly divorced Rhonda, haunted by her sister Evelyn’s ghost, travels to an old palazzo in Rome to confront Marco, the man who stole her sister’s heart—only to find out he’s vanished in the wake of Evelyn’s death. Meanwhile, Rhonda’s nineteen-year-old daughter Olivia, adopted by Rhonda at birth, travels to the mysterious and lush waters of northern Vietnam, where she’s been summoned by the missing Marco—a man she only knows from her parents’ whispers, a man she has never met or seen.

Soon, truths are exposed and lives unraveled, and the real journey begins. Four lives in all, spanning three continents, are now bound together in an unfathomable way—and they tell a powerful story about love in all its incarnations, filial and amorous, healing and destructive.

Very interesting article and, I must say that the feeling I had had left after reading your books is that of having being away..

And it was surprising, as I am Italian and I read 2 of your books while being an expats in Sweden:)