During Black History Month this past February, we took a close look at how authors present racial and cultural issues in their work—particularly when it comes to YA. It’s important to touch base on these important and often controversial issues to strike a chord within readers, raise awareness, and discuss history.

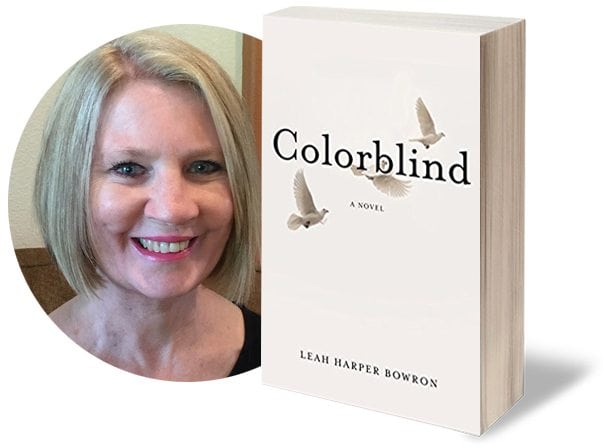

We tapped into the brain of YA author Leah Bowron for this piece. As a lawyer and a James Joyce scholar, Bowron’s article “Coming of Age in Alabama: Ex part Devine Abolishes the Tender Years Presumption” was published in the Alabama Law Review. Her debut, Colorblind, is coming out July 11, 2017.

I have a second skin which I wear when I write. No longer am I Leah Harper Bowron, a 60-year-old Caucasian woman with a pronounced Southern drawl. Like Clark Kent who has donned his superhero’s costume, I am now Miss Annie Loomis, a 60-year-old African American woman who lives in the pages of my book Colorblind set in Montgomery, Alabama in 1968. And as Miss Loomis I am scared—scared to be teaching at an all-white public elementary school and scared to be living in the heyday of the civil rights movement.

How did this transformation take place?

Gradually, very gradually.

I liken the process to that of an actor getting into character before a performance. Wardrobe is key. I picture what Miss Loomis will be wearing in the book, then her face takes shape, and her body falls into place. Makeup is also essential. I picture what makeup Miss Loomis will be wearing in the book, then her face takes definition. I then step into Miss Loomis’s shoes and take a stroll in her neighborhood. I picture her house and the furnishings therein. I then transcribe these mental pictures into the written word, and a book is born.

Yet I faced special challenges in the creation of Miss Annie Loomis. The most glaring challenge is the difference in skin color between me and my character Miss Loomis. How can a 60-year-old Caucasian woman from 2017 possibly slip into the skin of a 60-year-old African American woman from 1968? This question can be partially answered by my reliance upon historical fact in the creation of this fictional character. Miss Loomis is based in part upon my actual sixth-grade teacher. I cannot remember my actual sixth-grade teacher’s name, but she was an older African American woman teaching at an all-white public elementary school in Montgomery, Alabama in 1968. I remember how my sixth-grade teacher looked, and these details formed the basis of Miss Loomis’ physical description in the book. Although I don’t remember the exact words my teacher used, I do remember that she pronounced her words distinctly, and this attribute was given to Miss Loomis in the book.

Although historical fact may have shown me the way Miss Loomis looked and talked, it did nothing to bridge the color barrier which I faced as a writer. To try to slip inside Miss Loomis’ skin, I first had to dust off the images of African American women from my childhood in the 1960s. Some of these images were those of maids serving in white households, and these images helped shape the African American character of Ozella in Colorblind who was employed as a maid in the Parker household.

Unlike Miss Loomis who served as a main character in the book, Ozella served in a supporting role. It was easy to slip inside Ozella’s skin to fashion her character because my family employed African American maids during my childhood. I remembered how they looked, how they dressed, and how they talked. These memories were vivid and filled with love. I gave the character Ozella a detailed physical description and placed her in loving scenes with one of the book’s heroines, 11-year-old Lisa Parker who is based in part on me. To develop fully the character of Ozella, I did make Ozella the victim of racism—the racism which character Penelope Parker revealed in talks with her daughter Lisa. Lisa did not agree with her mother’s racism and stood up for Ozella throughout the book.

Miss Loomis was different from Ozella. She was more educated than Ozella and most of the African American maids of my youth. Miss Loomis, moreover, was physically frail unlike Ozella who was physically strong. I had to dust off an image of an African American woman I met as a lawyer to aid my creation of Miss Loomis. The woman I met was a board member of the Alabama Prison Project in Montgomery. She was well-educated and quite articulate about matters involving civil rights. She was also older and frail. She would serve as the perfect character sketch of Miss Loomis. And she did.

I now had a voice for Miss Loomis. She would speak distinctly but not condescendingly to her students. And she would discuss civil rights with her mentor, the African American supporting character Rev. Reed. It was easy to slip into the skin of Rev. Reed to create his character because his character was loosely based upon several civil rights leaders from the 1960’s. My character was different from his famous forbears in his oftentimes ruthless pursuit of racial equality no matter the cost. Rev. Reed sometimes pushed Miss Loomis into situations which frightened her. This unmitigated zeal spotlighted the imperfections existing on both sides of the civil rights movement.

Despite my educated character model, I still had difficulty slipping into Miss Loomis’ skin. It seems that prejudices from my past kept rearing their ugly heads to thwart my attempts to slip into Miss Loomis’ skin. I grew up in a culture which erroneously believed that the white race was superior to that of the black. Although I abhorred that prejudice and embraced my sixth-grade teacher, my dreams would often be haunted by that prejudice. I would dream of the scary Ku Klux Klansmen with their burning crosses and hanging bodies. I decided to turn that negativity into the prejudiced voices of the two schoolyard bullies in the book whose ghost-like Halloween costumes resemble a Ku Klux Klansman’s robes.

This prejudice is continued in the words and actions of some of Lisa’s teachers, and some of Lisa’s classmates and their parents. These characters are portrayed in a very negative light in the book to show that racial equality trumps prejudice. Having put my childhood prejudice to bed, I could now slip into the skin of my book’s other heroine, Miss Annie Loomis, and write. And what I wrote took my breath away.

I wrote about a 60-year-old African American woman who was so excited to be teaching white children that she put up a bulletin board depicting racial equality in her classroom. I wrote about an African American woman who dedicated her life to teaching and the civil rights movement. I wrote about an African American woman who could make books come to life before her students’ eyes. I wrote about an African American woman who baked cakes for the Halloween cakewalk and school open house. I wrote about an African American woman who bought a trophy for the winner of the sixth-grade spelling bee. I wrote about an African American woman who could empathize with Lisa as the victim of the bullies’ teasing about her cleft palate and cleft lip. And I wrote about an African American woman who was the victim of the bullies’ teasing about the color of her skin.

It was painful to stay in Miss Loomis’ skin near the close of the book, because I wrote about an African American woman wracked with fear and fighting for her life as a teacher. And I wrote about an 11-year-old Caucasian girl who tried to save Miss Loomis from the evils of racism. It was a profound joy for me to write Colorblind.

My second skin, Miss Annie Loomis, helped me find the truth.

Colorblind, Leah Bowron, July 11, 2017

The time is 1968. The place is Montgomery, Alabama. The story is one of resilience in the face of discrimination and bullying. Using the racially charged word “Negro,” two Caucasian boys repeatedly bully Miss Annie Loomis–the first African-American teacher at the all-white Wyatt Elementary School.

At the same time, using the hateful word “harelip,” the boys repeatedly bully Miss Loomis’s eleven-year-old Caucasian student, Lisa Parker, who was born with cleft palate and cleft lip. Who will best the bullies? Only Lisa’s mood ring knows for sure.

Leave A Comment