“We are either going to become a community, or we are going to die.”

In college, my mother found a teacher and a mentor in the renowned artist, educator, and social justice advocate, Sister Mary Corita (1918-1986). Corita drew this quote by Barbara Ward into one of the serigraphs she is famous for, though most of her writings were her own: “Not all of us are painters but we are all artists. Each time we fit things together we are creating—whatever it is, to make a loaf of bread, a child, a day.” Corita inspired a generation of women to live boldly, creatively, and freely. To express themselves through their art.

My mother was one of those women. Even though she baked no bread, and she made no art—as far as I could see at the time. She did make children. Four of them. But no bread. In fact, my first vision of my mother is through the mesh of my playpen, in her pencil skirt and heels, headed off to work.

For so many years I could only see my mother from this vantage point. Her leaving. Me watching her go. As it would be, when I started writing fiction as an adult—family dramas mostly—my mother characters tended to be narcissists. There were the angry years, the eye-rolling years, then, the writing years. I’d come to love and respect my mother by this time and yet still, I couldn’t see her other than through a daughter’s lens. In other words, all that she didn’t give me: home-cooked meals, rides to school, a presence at my games, a mom who hung with the other moms and joined the PTA. I fell into the writer’s trap of “everything she wasn’t.” In other words, it was all about me.

So then, who was the narcissist?

Oh, how I have learned so much as a writer by writing about my mother. How I’ve learned so much about mothers by writing about my mother—they, on the front line of battle, first to take the fall. We, their writer daughters, first to push them off the ledge.

I want to suggest to young writers not to fall into this trap—but part of me understands that I had to exorcise all that other stuff out of my system. It took a few books worth of mother narcissists before another mother began to evolve in my writing. Mother as woman. Mother as leader, forager, pioneer. Mother who couldn’t be at my games because she was MAKING A LIVING. Working and learning and growing. MAKING MISTAKES. Evolving, creating, changing, reinventing herself as a woman so that she, and therefore we, her daughters, when faced with making hard choices about work, marriage, children, life, we had someone to look to as an example, someone who went over the ledge before us. Not always pretty, happy choices. But choices right for her, us, women.

As writers, it’s our duty to keep searching, digging, finding the balance in our characters. Being honest. Not just with our readers, but with ourselves.

Never, ever, stop searching for your mother. There’s always more to learn, cull. Listen to her. Let her teach you. If you think she has no more to give, you are wrong. Ask questions.

I only learned recently that my mother’s grandmother divorced her husband at a young age, became a teacher to support herself, and went on to raise her son in a house with other self-supporting women, where she lived until her death. “She made a big impact on me,” my mother told me. My jaw dropped open. My mother and I have become close. We talk often. She’d never once spoken of a grandmother. Another question would be, why I hadn’t asked.

There’s a reason why strong women are strong women. And it’s usually because of the strong women before them.

Fierce women dominate my novels now; call them narcissists, call them nasty women, call them whatever you want. Searchers, dreamers, women both hardened and vulnerable—tenacious, complicated, imperfect women. Relentless women. Messy women. Women unafraid to reinvent themselves. Women who do not quit. Women who love deeply, and so therefore hurt deeply. Women who survive. Big, bold, beautiful women, not in the traditional sense but, for instance, in the Olympic champion sense, aka women Michelangelo might have carved statues of.

“Creativity belongs to the artist in each of us,” Corita wrote in another serigraph. “To create means to relate. The root meaning of the word art is ‘to fit together’ and we all do this every day.” My mother and I create together just by relating on a deeper level, my sisters too, and consequently my characters are blossoming, maturing alongside my relationships with these women, with all the women in my life, a community of women, sharing, learning, and growing from one another, “fitting together.” There’s now an honesty in my characters not there before.

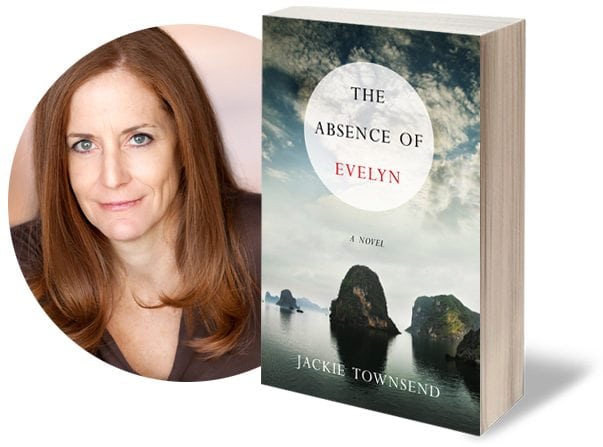

Jackie Townsend is the author of The Absence of Evelyn (SparkPress, April 2017), and the award-winning author of Imperfect Pairings. A native of Southern California with an MBA from UC Berkeley, she is a management consultant turned author. Married to an Italian and incessant world traveler, Townsend spends a lot of her time in places not her own. As the youngest of four children, she carries a strong sense of family with her to these places, often foreign, and writes about belonging (or not belonging), loss, and love. She lives in New York City with her husband, and sometimes they are even there at the same time.

About The Absence of Evelyn

Newly divorced Rhonda, haunted by her sister Evelyn’s ghost, travels to an old palazzo in Rome to confront Marco, the man who stole her sister’s heart—only to find out he’s vanished in the wake of Evelyn’s death. Meanwhile, Rhonda’s nineteen-year-old daughter Olivia, adopted by Rhonda at birth, travels to the mysterious and lush waters of northern Vietnam, where she’s been summoned by the missing Marco—a man she only knows from her parents’ whispers, a man she has never met or seen. Soon, truths are exposed and lives unraveled, and the real journey begins. Four lives in all, spanning three continents, are now bound together in an unfathomable way—and they tell a powerful story about love in <em>all</em> its incarnations, filial and amorous, healing and destructive.

Every time I hear you talk or write I discover a new you. Well done Jackie!