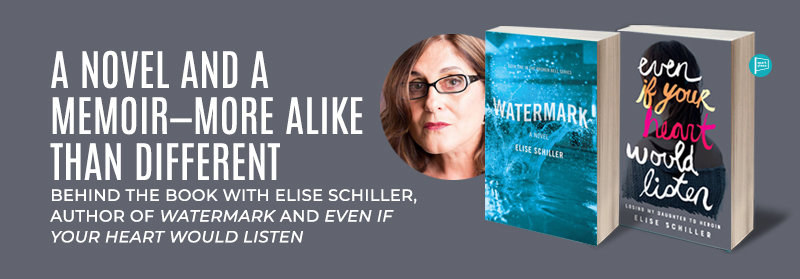

In the past year I’ve published both a novel and a memoir. What’s the difference in writing the two? Many readers assume that the two genres are very different: that memoir is true, and that fiction is, well, fiction. Not exactly.

We do expect memoirists to recount incidents that actually occurred, but we must acknowledge that those incidents are curated. My memoir, Even If Your Heart Would Listen: Losing My Daughter to Heroin, is about the overdose death of my daughter, Giana Natali, in January 2014. She was almost thirty-four. Parts of the book recount scenes from Giana’s childhood, events of decades earlier, that I selected specifically because they either gave some hint of the troubles to come, or because they illuminated my relationship with Giana in the context of what came later. The key word here is selected: I had very specific reasons for choosing what I did. Had Giana not died, and I were writing a memoir about her swimming success and my life as a swim mom, I would have selected different vignettes. All of these events happened, but context is everything. In my memoir, I make the observation that many small moments in my relationship with Giana would have been forgotten if not for what happened later.

Criminal lawyers understand very well that memory is fallible. Five witnesses to the same event may give very different accounts of what happened. In memoir, past events, sometimes long past, are examined through lens of all that has occurred between then and now, so we do not see the past as it happened, but as we interpret it now. And can any of us, no matter our desire to be accurate, discount the role that pride, joy, shame, guilt, or regret may play in our interpretation of the past? Perhaps one difference in writing my memoir and my novel is that with the memoir, I felt the need to be honest about the events as I remember them, while accepting the possibility of distortion and omission. In my novel, Watermark, I only felt the need to be faithful to the truth of the world and the characters I had created.

But was that world totally invented? Of course not. Watermark borrows from events that have occurred in Philadelphia, where the book is set; it relies on my thirty-year career working in children and family services in Philly; it takes advantage of my significant experience with competitive swimming. There are also small and subtle ways in which my novel mines my life—maybe the way a character walks or the look of an urban street in a certain kind of light draws upon my memories.

Is fiction ever really just fiction? Take a speculative novel like The Handmaid’s Tale. Margaret Atwood has famously said that she didn’t include anything in that novel that hadn’t already happened in the real world: sexual slavery? Societies fashioned on corrupt theologies? People forced into containment camps based on race, ethnicity, or religious belief? Yep, all this has happened. Of course, Atwood refurbished these atrocities for the novel’s purposes, but they are certainly based on real events. Even in a historical novel removed centuries from the present, writers draw upon their own experiences and knowledge. It’s quite evident that Diana Gabeldon used her academic background in biology to create the world of seventeenth-century medical practice and herbal healing in the Outlander series. Steamy sex translates quite well from the present to the sixteenth century, and apart from what the bedchamber might look like, doesn’t need to be invented. Ironically, a writer might feel more freedom to draw upon her own sexual experiences while writing fiction than while writing memoir.

In matters of craft, I labored with structure just as much with my memoir as I did with my novel. In second and third drafts of both books, I radically rearranged start points and the order of scenes. I also played with voice in both books. Some scenes in my memoir are written in direct address to my daughter, while others are written in standard first person. In the first draft, I hadn’t included those direct address segments. I began writing my novel in third person but switched to two first person narrators. This was as challenging as the changes of tone I felt necessary to make in the memoir, as I switched from personal topics to explanations about addiction and drug treatment. I also made many edits to the language in both books, and paid as much attention to imagery and figurative language in the memoir as I did in the novel.

Perhaps the difference between memoir and fiction often rests with intent. Fiction is often written primarily to entertain, and memoir is often written to instruct and inspire—this is what I experienced, how it changed me, and what I learned. Still, with my two books, that line is hazy. I want my novel, Watermark, to describe a world right under many a reader’s nose, but one that is likely unknown to many readers. And I want that reader to come away with insight and a sense of compassion for my characters that is new. I cried for my daughter and myself while writing my memoir, but I also cried for the characters in Watermark.

So where does this leave us? I believe we conclude with the acknowledgment that both genres are art, and art by definition is something one creates and shapes. Despite their differences, memoir and fiction are close cousins.

Leave A Comment