My take on writing a historical novel is pretty basic. You start by finding your own unique voice, and this may require many hours of experimenting. I’ve switched back and forth between cozy mysteries and historical suspense, but the same rules apply. Story is key. The reader must become engaged with the characters and really care what happens to them.

Now comes the challenge. For the historical novel, it’s essential find the right balance between creating an imaginative plot and bringing in specific events and well-known names, like Washington and Lincoln. For me, the aim is to immerse the reader with a strong sense of being in a certain time.

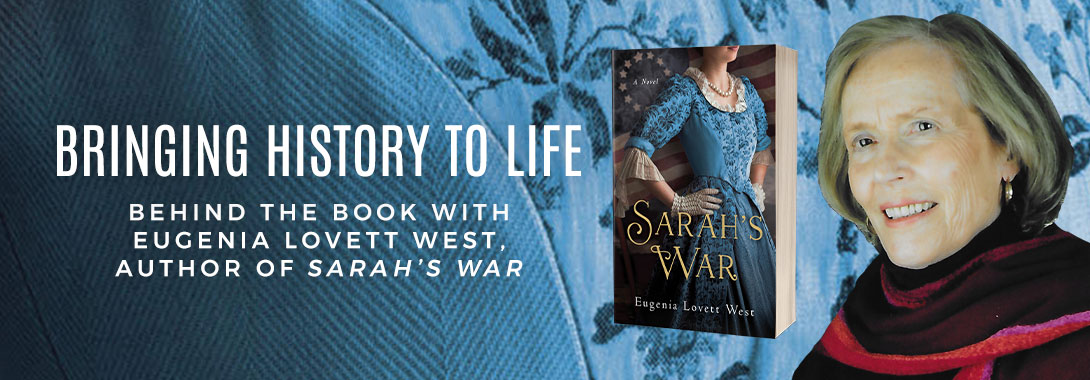

Writing a book is a big investment in time and energy, so where to start? Some writers have a deep interest in a particular period of history. Some have sudden inspirations. My latest novel, Sarah’s War, was inspired by an account of an event that took place in 1778 in our war for independence. British officers had been enjoying winter quarters in Philadelphia while Washington’s untrained militia were dying and deserting at Valley Forge. To honor the departure of General Sir William Howe, his officers put on an entertainment called the Mischianza. It involved a medieval tournament with jousting knights, followed by an epic ball and fireworks. Nothing as extravagant as this had ever happened in the colonies, and reading about it started me on a long and unexpected journey.

Research is key, and much depends on the period and the place. My first historical novel, The Ancestors Cry Out (Doubleday) was set in Jamaica, WI. The period, 1870s. The place, a sugar plantation. It didn’t take more than unearthing a few journals written by English governors’ wives and some knowledge of voodoo to create a story.

Not so with Sarah’s War (SparkPress). Because this took place during the American Revolution, any mistakes would quickly be noted. I spent four days at the Brandywine River studying the battlefield. I could tell you the positions of both British and Continental Army troops, and that Washington’s lack of intelligence nearly cost him the war. I did extensive reading at Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library. Details are important—what people wore and at what times they ate.

There are, of course, easier ways to get background. The internet is a help, and so is feeding off the valuable work done by non-fiction historians. On the other hand, it doesn’t hurt to be a little skeptical. Much of history is slanted toward a writer’s political beliefs. The way the English King Richard III is now perceived serves as an example.

In the end, though, I had to remind myself that I’m a story teller, not a historian. I seem to gravitate toward strong women working their way through challenges, no matter what the time frame. As much as it hurt, I made really drastic cuts, including most of the Battle at the Brandywine. Sarah and her life of deception and heartbreak became the focus of a faster moving plot with a compelling background. It was a perilous time and we came dangerously close to losing that war.

Lately, I’ve come to realize how much both reader and writer benefit from the historical novel. We gain insights from expanding our knowledge about the past and the people who changed history—a never-ending source of interest that can lead to greater wisdom. To those who decide to go down this road—good luck and enjoy.

Leave A Comment