In books of fiction, redemption arcs are tied to a character—the protagonist, antagonist, or even a secondary character—and vary by the author’s intention, genre, plot, and characters. But, before we dive into that, let’s define the redemption arc.

The dictionary defines redemption as “an act of redeeming or atoning for a fault or mistake.”

In the definition, the word “act” implies action. Choices create action.

A redemption arc is when a character:

1) performs a heroic act that makes up for his previous wrongdoings (note: the character must need redemption)

or

2) is redeemed by another character

Is this always true? No.

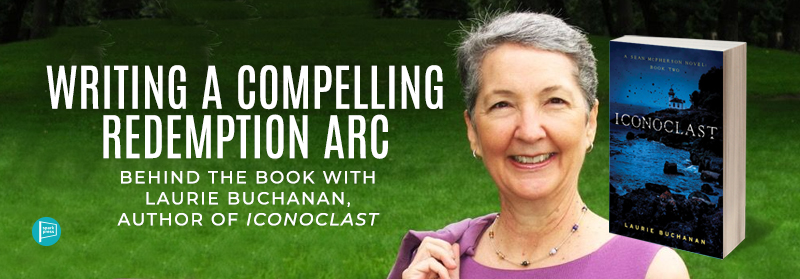

Experientially, readers know that there are exceptions. Take Sean McPherson, for example, in my series. He’s the ex-cop turned PI protagonist in the Sean McPherson novels. And while he has not done anything wrong, he believes that he’s responsible for his ex-partner’s death. Unfortunately, this belief has taken on the form and extensive weight of survivor’s guilt that tends to color his decisions—sometimes positively, sometimes negatively.

Readers ask if Sean McPherson is afraid of anything. Yes, he’s scared of failing others. Having experienced the horrific consequences of a violent crime (the one responsible for killing his partner), McPherson does not want anyone else to suffer similarly. He wants to make the world a better place; he wants to protect people before they even know there’s a threat.

McPherson’s greatest weakness and strength are the same—his humanity and empathy. These make him willing to fight fiercely for justice for others.

I leverage McPherson’s fear, strength, and weakness time and again throughout the storyline. Why? Because opening him to great pain and sorrow is the perfect catalyst for an arc.

The redemptive act can be external, internal, big, or small. The repercussion is that the action performed by the character helps make up for what s/he did (or believes they did) in the past.

Now let’s flip it. The protagonist can extend a redemption arc to the antagonist. Will they accept or reject it? Will it work? That depends on how well you know your characters.

So: how to write a redemption arc?

- I maintain a “Character Bible” where I detail each character inside out. Their backstory. What makes them tick. Their personality type. Their strengths and weaknesses (physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual). This information informs me if they’re the type of person who will work to redeem themselves or if they’ll accept redemption from another character.

- At the beginning of each scene, I reveal the character’s this-point-in-the-story goal. Then I create tension by introducing something (a person, place, thing, event, or opportunity) that opposes or obstructs their redemption.

- Introduce the character’s weakness. Remember: it can be physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, or a combination thereof. Does s/he go too far for those s/he loves? Does s/he allow themself to be held hostage by the opinion of others? Does the character recognize their weakness, or are they blind to it? If they’re aware, do they take action to change it? Or do they remain unaware, thus unable to work for redemption?

- Does your character react (kneejerk) or respond (thoughtful) when an obstacle is introduced? The answer is worth the price of admission because it reveals the character’s true colors—the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Redemption arcs are necessary because they offer hope to readers—sometimes even long after the last page is turned. One of my favorite redemption arcs is from Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize-winning All the Light We Cannot See.

The story takes place against the backdrop of World War II when a blind French girl, Marie-Laure LeBlanc, is charged with the task of protecting a prized blue diamond that the Nazis want. A German orphan, Werner Pfennig, works for the Nazis but is ultimately repulsed by their cruelty. Pfennig and his cohorts find LeBlanc and the diamond. But to seek forgiveness for the Nazis’ acts, he doesn’t let the diamond be taken, or LeBlanc be killed.

Redemption arcs aren’t one-size-fits-all. Instead, they’re unique to the storyline and characters. Readers love to love characters, and love to hate characters. A well-written redemption arc goes a long way toward satisfying their desires.

Leave A Comment