Truth is, I never thought of becoming a writer. I wanted to be a reporter, and for some twenty years, that’s what I was: a reporter of hard news. Give me one fact, two rumors, and twenty minutes and I’d give you 350 words.

Writing was a means to an end, and that end was the reporting. A well-written news story reported facts. It could be colorful, but with minimal literary flourishes. Clichés were banned (like the plague). Keeping it tight, shunning adjective, adverb, and oxymoron (like brutal murder) was gospel.

I reveled in being a reporter—not a writer.

Then I became an editor. Perspectives changed. I worked for United Press International (UPI), a news agency. Our “core audience” was several hundred newspaper editors who had the option of choosing our versions of the top stories of the day or those by our archcompetitor, the Associated Press or AP.

Stories were rarely lost on the reportage of essential facts. Rather, editors chose the version that most appealed to them—that is, how well the story was written. I came to understand the real art of the job was being a creative writerwithin the structure of journalism, like a Marsalis brother exploring the limits of jazz.

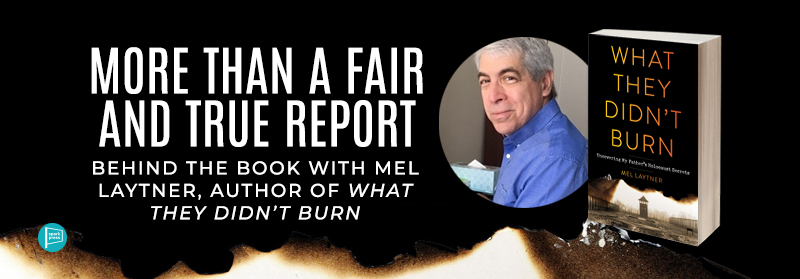

In retrospect, this training helped prepare me for the discipline required to write What They Didn’t Burn, about my odyssey tracking down a Nazi paper trail that revealed my father’s Holocaust secrets.

Early on, friends and colleagues warned that I’d have to publicly explore my innermost motives and feelings about my late father. I’d protest that my “project” required no such heavy lifting. It was simply an exercise in investigative journalism 101: I had uncovered startling, rare Nazi documents and tracked-down eyewitnesses that, together, made for a compelling story.

Turned out everyone was right and I was wrong. To connect with readers, a memoir must be more than, as the libel lawyers say, a fair and true report. It must be about people more than papers. Emotions matter. Writing about them is hard. At least it was for me.

Like when I found the Auschwitz “punishment protocol” that sentenced my father to 25 lashes for selling 15 diamonds on the black market.

I had read enough survivor accounts to know how this worked: Dad would have been bent over a bench, his trousers pulled to his ankles. A whip or rod would strike his bare buttocks twenty-five times. He likely would have passed out before the last blow. Fellow prisoners would have dragged him back to his barrack and applied whatever poultice was available.

The document itself was stunning—two pages of Gothic font, fill-in-the-blank spaces and check boxes, all properly signed, initialed, and rubber stamped, all to justify utter barbarity.

As a writer, I felt obliged to “show” my reactions—shock, outrage, pain. After all, every memoir workshop I had ever taken stressed the need to show the reader how you feel.

Still wrestling with this, I spotted a notation at the bottom of Page 2, that the sentence was carried out on Thursday, June 29, 1944, by fellow inmate—and listed the prisoner’s name and Auschwitz tattoo number.

Qualms about voice or language dissipated faster than warm breath on a winter’s day. Returning to my reporting roots, it became an exercise in less being more.

Who was this man? Was he ordered to beat my father, or did he volunteer, perhaps for an extra ration of camp soup that night? What made a man like this tick?

Following leads and hunches, I tracked down documents and concentration camp survivors who remembered this prisoner well—a Dutch Jew from Amsterdam who became a kapo, a prisoner trustee. But the deeper I dug, the more complicated his story became.

In retrospect, the only way to write about this was to keep my emotional distance.

I wish I could say this decision was instinctual. It was not. In too many drafts, I tried all manner of evocative language to convey my feelings. It was no good. The words sounded artificial, forced; the sentences suffered from too many adjectives and adverbs.

Luckily, I had powerful, compelling material that could carry the narrative forward. The hardest part was getting out of the way and letting the story tell itself.

Leave A Comment