Back in the late sixties, I had a chance to see the Incredible String Band at the Fillmore East in New York. One of the things I remember about that show was how all the people in this band would just leave their position and go pick up another instrument and play it like that was the one he or she had been playing all night. They’d do it in between songs, and sometimes even within the same song. One guy would be up there with a mandolin or something, then put it down and walk all the way across the stage and pick up an oboe and start playing that while everyone else in the band was doing the same thing. Which could be why they called themselves incredible, something I hadn’t considered until now.

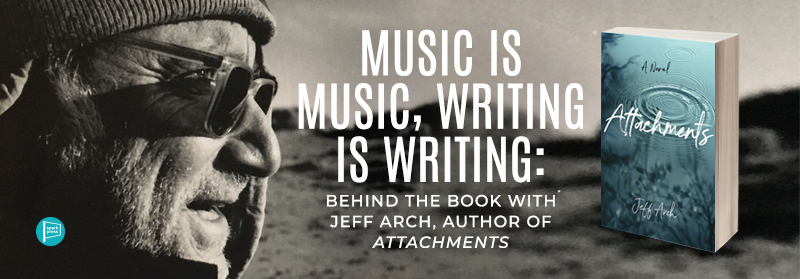

When asked how I would describe the transition from writing screenplays to novels, I always think of how the Incredible String Band crisscrossed that whole stage all night, trading off instruments like business cards.

I thought, musicians are musicians. And if they can do that, then it must be possible to switch from one form of writing to another.

The Limitations of Switching Instruments

There are certain kinds of writing I most definitely cannot do—some I can’t do well and others I can’t do at all. When I look for a pattern, it’s pretty simple: if something involves people and dialog and a story, I can take a good stab at it. It’s like switching instruments in the same category—fiction—and staying away from categories/instruments that don’t speak at all to the way my brain works. A movie and a novel and a play are all different ways of writing a piece of fiction. They have different formats, and different demands particular to their form, but in essence they’re still stories, and I wanted to be the kind of storyteller who could play more than one instrument. None of the formats themselves are especially hard to learn, and yet none are easy to master. And the reason I’m glad I can do it, to whatever degree, is because there were times something I was writing wasn’t working and driving me crazy—until it hit me that it wasn’t working on purpose, and driving me crazy on purpose, to get me to finally listen and write it another way. Those pieces would have never happened if I didn’t grow some versatility.

From Movie to Novel

Attachments started as a movie and I couldn’t get it to work. Years later, it came to me that the reason it didn’t work as a movie is because it wanted to be a book. I didn’t set out to write a novel—I set out to write a story that wasn’t going to let go of me until I did something about it. Once I had that revelation—that this story wanted to be a book instead of a movie—and was trying to tell me that for years, I saw the whole thing open up. The story took life, and I was able to tell it the way it wanted to be told: alternating voices and back and forth in time. Prose, and not screenplay language. People’s thoughts, not just their actions.

Lessons from Screenplay Writing

All the training from screenplay writing—the discipline, and economy of style, and the rigors and demands of the form itself—those habits kept me on point the whole way through the novel. How to keep a story moving.How to write for one reader, rather than a dozen different committees who are using your document as a blueprint, taking the information they need from it and then going and doing their thing. In a screenplay, you’re writing for a cinematographer, an art director, a production designer, a composer, a director, actors, props and electrical departments, a production manager who’s got to figure out the logistics of the whole thing, and producers who swear they don’t have the money for what you’re trying to do.

Tools for Writing a Novel

In a book? It’s mano a mano. One writer, one reader. No movie tricks, just plain old storytelling, where the only rule seems to be Keep The Story Moving—which is what all my movie training was about anyway. Not that it was an easy transition, but I’m a thousand percent convinced it would have been much more difficult to do the other way around, to cross from novels over to screenplays. It’s the same job, with different tools—sometimes vastly different—but that’s the whole point of the craft. To grow, to expand, to gather new tools and know how to use them.

It can be hard for some novelists to think cinematically, at least about their own work. But thinking cinematically while writing a novel is a fabulous tool. Imagery, brevity, that constant ticking clock that demands things keep happening, event to event. When an event can be as small as someone leaving a backpack behind, or someone else needing a bigger boat because a great white shark is taking bites out of the one they’re on. Events force behavior. And stories are about events.

Leave A Comment