There are several reasons why writers choose to write autobiographical fiction or memoir:

- The story of our life is the one we know best.

- English teachers have been forever telling us “write what you know.”

- We feel compelled to tell our story.

- We think our lives have been interesting and might have something to teach, or at least entertain, others.

- Revenge.

- Redemption or reconciliation.

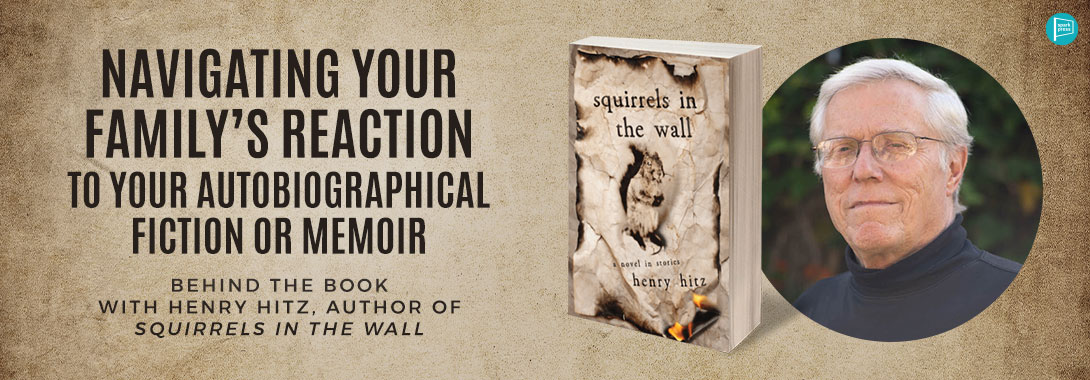

I’m sure there are more. Certainly, the question of how one’s family will react gives a lot of writers of memoir and autobiographical fiction pause, forcing many a manuscript to languish in the drawer. One way I found to get around this pitfall in my coming-of-age novel-in-stories, Squirrels in the Wall, was to write about the habitat where I grew up from the point of view of different animals who lived there, including humans. This approach removed the autobiographical story from the realm of realism, mitigating the tendency of readers in my family to see themselves in the characters.

“Portrayals “

I often feel the need to lecture readers on the meaning of the word “fiction” and remind them of the statement under the copyright date, “any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.” Sometimes I add that all writers are assholes who steal the identities of friends and family and twist them around to suit the demands of the narrative. This does not mollify everyone. Some people will stay pissed off at how they were “portrayed” no matter what. It helped that the primary antagonist of the stories in Squirrels, the father, is based on a person who is long dead.

Example: Death Masks

He wasn’t always, though. Once, when my father was in rehab from his stroke, I read him “Death Masks,” a story narrated by the ghost of the protagonist Barney Blatz’s grandfather and the antagonist’s father (how’s that for distance?). The character based on the father is relatively sympathetic, I thought. I had forgotten this scene:

One day, as the pitch of the tank lowered toward winter, Barney the second appeared in the shack so seething with anger that, to the grandfather, it looked as if his aura were on fire. It was difficult to piece together the story. There had apparently been some confrontation with his parents. “How dare them!” he said to the cat. “I hate them! I hate them! They know I want to go to Chicago with them. They know I have to see that V-2 rocket they have at the museum. I told them! But no! They say I have to stay here with Pookie and Mrs. Chipmonk! How can they do this?” He grabbed the cat and looked as if he was about to slam it against the wall. Alarmed, the cat jumped out of the boy’s hands.

As I read aloud, I stumbled over the words “I hate them.”

The Humanity of Animals and the Animality of Humans

Using the animal perspectives in what is, in essence, a family drama enabled me to reach feelings too fraught to write well about directly. It also put a fuzzy frame around the dysfunction of the Blatz family, softening the impact, sometimes ironically. I like to think of the book as the cutest novel ever about death.

For example, in “Life Cycle of a Toad” the boy protagonist captures a toad named Bipy and puts him in a jar as kids often do. After a while, the boy returns the toad to the woods. When Bipy tells his toad friends what happened, they don’t believe him. In this way the toad story parallels the human story of abuse which no one believes. The abusive relationship between humans and animals reflects the abuse of children by adults.

The novel is about the humanity of animals and the animality of humans. It turns the scientific aversion to anthropomorphism on its head by assuming that animals—all animals—are exactly like us, except in ways that they demonstrably aren’t, like walking on two legs or writing novels. It has long been clear to me that the arrogance of the human species is threatening the survival of the planet.

The use of comedy can also blunt the edges. One of my stories is about how the father forces his son to drown the illicit cat, to which the father is allergic. Telling the story from the point of a dog who hated the cat at first but had grown fond of it gives the otherwise horrific scene a comic poignancy.

When people have strenuously objected to how a character based on them was portrayed in one of my stories, I sometimes once again revert to my inner asshole and tell them, “You know, it’s an honor to be in my book. You are now immortal. Congratulations.”

Henry, you have invited us to see the world differently. The intermingling of humans and animals broadens our understanding of our home. No doubt challenge but I hope satisfying.