My mother is disappearing. Physically, she still looks my mother—maybe a bit thinner, but basically the same. But when I look into her eyes, the sparkle is gone. Two years ago, she started forgetting things. Birthdays, appointments, where she put her keys. Getting her to a neurologist took some convincing, but when she finally made it there, the answer was straightforward. My brilliant, independent, no-nonsense mother heard two words no one ever wants to hear: Alzheimer’s disease.

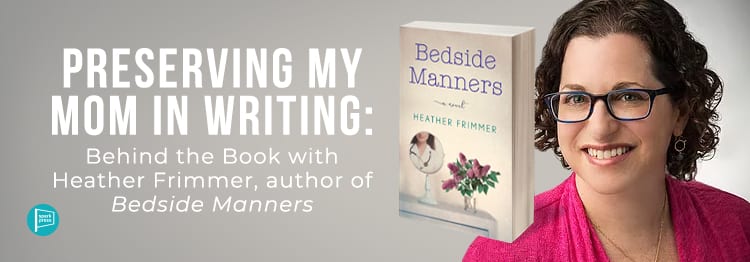

At that time, I was in the midst of drafting and editing my debut novel. Bedside Manners touches on several different angles—it’s a medical story about the emotional repercussions of a cancer diagnosis, a coming-of age-narrative, and an exploration of the difficulty of interfaith relationships—but above all else, it’s a mother-daughter story. The relationship between Joyce, the mother, and Marnie, the daughter, is the core of the novel and their connection is what stays with readers long after they turn the final page.

Many people have asked me whether Joyce and Marnie’s relationship is based on my own relationship with my mother. The funny thing is, I didn’t set out to write a mother-daughter story and I certainly didn’t consciously model Joyce after my mother. But now that the book is released and I have a bit of distance, I see a surprising number of similarities in their personalities. As I reflect on my mother’s decline and the writing of this book, I realize that no matter what intention you have for a character, it can be cathartic to channel that energy into your writing. Maybe I didn’t realize it at the time, but it’s something to take note of as writer: observe your characters, see who they relate to in real life, and build on that inspiration to make the characters authentic and the story a mirror of reality.

When I look closely at Joyce’s personality, I find a number of remarkable parallels between her and my own mother.

- Joyce is fiercely independent, strong, and not afraid to stand up for what she believes in. In the late 1960s, my mother was one of the first women to attend a previously all-male engineering university. Having to constantly prove herself to her male classmates and professors hardened her resolve and made her stronger. She could do whatever she wanted to do and no one would stop her. She went on to become the vice president of a non-profit company and she passed her strength on to me. She never allowed anyone to tell me that I couldn’t do something just because I was a girl.

- Joyce doesn’t have much use for female friends. She’d rather be alone than have to listen to silly conversations and make small talk. My mother often says that she doesn’t enjoy spending time with women because they talk about fluffy things. She has no use for surface conversations and would rather get to the heart of the matter than talk around it.

- Joyce has no patience for materialism and vanity. She doesn’t understand why people whiten their teeth or straighten their hair or choose to get breast implants. She doesn’t care what people wear and she has no use for make-up. Similarly, my mother has never colored her hair and on the rare occasion she shops for clothing, comfort is the most important criteria. She is who she is—take her or leave her.

- Joyce prefers to keep to keep her emotions private. Sharing her feelings makes her feel too vulnerable. Crying in public is something to be avoided at all costs. My mother also keeps her emotions close to her chest. I can’t remember ever seeing her cry, even at her parents’ funerals, and though I know she loves me, she very rarely proclaims her love.

- Joyce would do anything for her family. Even though her children are grown and living their own lives, she thinks about them constantly and makes her decisions based on what she thinks is best for them. Family connections are very important to my mother as well. These days, she seems most comfortable when she is on the floor playing with her five grandchildren.

- Their names both start with the letter J. I swear I didn’t do this on purpose, but it can’t be a random coincidence, right?

The disease has definitely progressed in the two years since my mother’s diagnosis. Her voice is quieter and more tentative, she gets incredibly anxious about small things, and carrying on a full conversation is a challenge. Her answers to questions are short and she is often unable to reciprocate. When she does ask a question, she repeats the same one over and over. She no longer drives and is entirely dependent on my father to help her navigate the world. Every day, she is a little bit less my mother and a little bit more the disease.

Right after I learned the diagnosis, I had a long conversation with my medical school roommate who also happens to be a neurologist. Knowing that I would prefer truth over sugarcoating, she told me that my mother will be okay for my twelve-year-old son’s bar mitzvah planned for this coming March—that she will still remember her grandson and be able to enjoy the day—but by the time my ten-year-old makes it to his momentous day, she probably will not recognize him. Though it was hard to swallow, I appreciated my friend’s candor. I would much rather be prepared than close my eyes to reality. When I mentioned the name of my father’s sister during a conversation last week, my mother kept repeating her name without a hint of recognition in her voice. My friend’s upsetting prediction will likely prove true.

With my mother fading away before my eyes, I’m thankful I put so much of her into Joyce’s character, intentional or not. Long after she no longer recognizes me—I know that day will eventually arrive no matter how much I dread it—Joyce will live on forever in the pages of Bedside Manners.

Leave A Comment