In August of 2015, four years after my mother died, I was driven to look for clues to the mystery of her life. I knew the outlines: Betty Pembroke Heldreich Winstedt was born in 1913 and died in 2011. She came from pioneer stock in Utah, fled a middle-class family life in Chino, fell in love with surfing at age forty, and outlived two husbands and a few lovers. She was and is admired by surfers worldwide. I knew the two of us were confidantes, and she was certainly my role model. But it had started to sink in just how many questions I’d never asked her.

One day, I discovered a tattered cardboard box hidden on a dusty shelf in our garage at Makaha Beach. I wrestled it off the shelf and found a forgotten trove: what my mother called her “autobiography”—written to cover her years from birth to age twenty-four—along with her collection of memorabilia, letters, and photos spanning the rest of her long life. Her secret writing projects recounted a life that shows a philosophical bent and a spirit of adventure—indeed, a daring that continued into her last years. But there were still gaps.

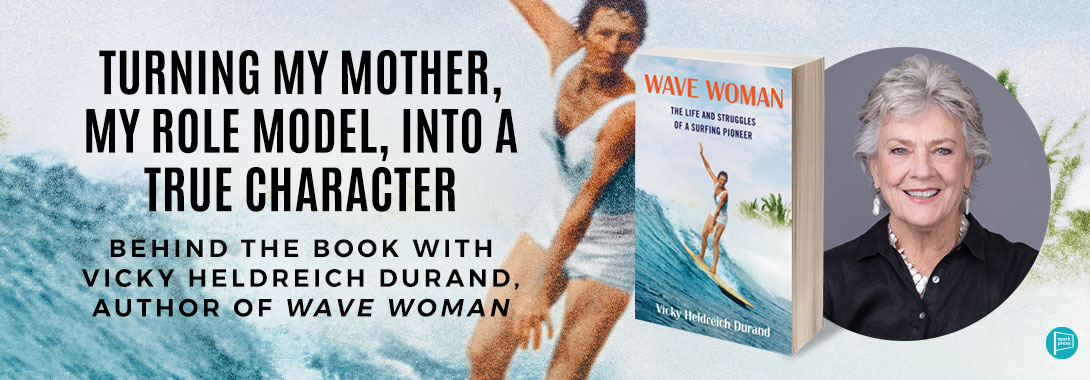

To fill them in, I embarked on a dual journey of discovery. The first part of my quest was to find detailed information about my mother’s life and learn how her unconventional example shaped others—and, of course, me. The second part was to deepen my understanding by writing about it. And not just in a private journal, in a book. A great book—to honor my mother’s legacy and to share this understanding with others.

Writing

I struggled with the writing. Eventually I had eked out 45,000 words, but I was lost. The story was flat; I hadn’t rendered my mother on the page. A friend suggested Constance Hale to help me shape the story and make it into a professional volume that would sit in libraries and sell in bookstores.

I started working with Connie, who was an experienced book editor and an accomplished writer. Her first round of editing focused on structure. She wanted to straighten out the chronology so that a reader could follow it.

Here’s what she wrote to me in her first memo:

Your best bet in this book is a pretty straight chronology. Sometimes you want to flash forward to a dramatic moment, something that sets the theme, and use it as a “hook” to open a chapter. Sometimes you might also want to flash back. But one of the advantages of chronology is that our sense of the character builds, and we get to know her. We see the way one thing leads to the next, and the way certain themes (like her athleticism and her sense of play) develop. Then, at the end, her aging will affect us emotionally. Let’s be careful about foreshadowing. Don’t tell us ahead of time that her marriage won’t work. Just tell the story: We want to see her commit, change, grow, get disappointed, and then make the big leap out.

It wasn’t enough just to put things in chronological order. Chronology can be plodding without other dramatic elements.My first drafts lacked two things essential in drawing the reader into the story: character descriptions and scenes. Connie had me strike clichés like “beautiful,” “wonderful,” “picturesque,” which I used repeatedly. “Paint the ‘beautiful’ scene for us,” she commanded. “Tell us what makes a place ‘picturesque.’” I began to do research, look at historic pictures, find news reports, and pick up a thesaurus.

Incorporating Description

I spent time trying to recreate the landscapes and landmarks of my youth. In the first draft, there wasn’t a single description of Makaha. I used our first drive out to our future home to give the reader a glimpse:

Sugarcane fields stretched from one town to the next. After a big rightward bend in the two-lane highway, there stretched before us a series of round hills, or volcanic tuff cones, that jutted out into the cobalt sea. We continued along the rugged seashore, past the towns of Nanakuli, Maili, and Wai‘anae. Gray-green mountains rose to the right, punctuated by spacious, mile-wide valleys. We passed bountiful farms, wooden shacks, and Quonset huts, all surrounded by gardens with coconut palms and plumeria trees flowering in pinks, yellows, and whites. We witnessed country living at its best; pigs, chickens, horses, and dogs lived largely unpenned in yards and fields.

After an hour’s drive, we arrived at Makaha Beach. This storied area lies at the foot of a great green valley carved like an amphitheater into the backside of the spectacular and most sacred spot on the coast, Mount Ka‘ala. At 4,040 feet, its craggy volcanic summit sits starkly against an impressive backdrop, an azure sky with phantomlike clouds. Mākaha Valley leveled out at the Pacific coastline; just below a craggy mountain softened by grasses lay a half-mile crescent of clean-swept, white-sand beach—the most beautiful strip Betty had ever laid eyes on.

The Shift from Mother To Character

Next, I had to stop thinking of Betty Pembroke Heldreich Winstedt as my mother and start thinking about her as a character. I consciously made a shift from daughter referring to her in an intimate way as “Mother,” to memoirist writing about “my mother,” and even to author writing about “Betty” with a detached eye.

Slowly, my mother became “Betty.” And I worked to become not a nostalgic daughter but a credible narrator.

Describing Betty

Part of this process was to take as much time and care describing my mother as I had with the landscape. I thought including lots of pictures would do the trick. But the reader needed clues as to how she moved through the world—not just her features, but her clothes, her gait, her demeanor. By the last draft, character descriptions were woven throughout. I tried to show Betty developing and maturing. Here she is as a girl:

Betty was humble and unpretentious. She had a deeper connection with her mining engineer father than she did with her striving mother. In spite of Betty’s striking looks—she had a strong, triangle-shaped nose and high cheekbones, greenish-blue eyes, chestnut brown hair, and smooth skin—she grew up feeling like the family’s ugly duckling. She was a tomboy, a natural athlete, and, most of all, a fierce competitor.

And here she is as a grandmother—her own kind of grandmother:

Betty had not lost her fascination with fast cars. To make the commute to her new jobs in Honolulu bearable, she bought a silver-blue Corvette. She happily raced around in it, dodging policemen along the way. (In the summer of 1970, she asked my daughters, eight and nine years old, whether they had ever gone one hundred miles an hour in a car. Betty then put her foot to the pedal.) Over a ten-year period, Betty’s Corvette was a major source of pleasure. Eventually, though, she tired of getting speeding tickets. Also, some neighborhood kids were putting sand in her gas tank. She decided to get less conspicuous wheels and bought a two-door black Cadillac Seville.

Applying the skill

As I became more adept, I applied every bit of skill I was developing to craft the most important moments of the book, featuring Betty on the Makaha waves she came to conquer. I picked a handful of rides that were highlights of the story, slowed them down, and wrote out the action. I went back to the thesaurus. Not for nouns and adjectives this time, but for verbs. Sometimes, I was writing not just about Betty, but about our relationship. That was the trickiest thing of all.

My mother Betty was an incredible woman and athlete. We both broke barriers in women’s surfing, winning big wave surfing competitions, such as the Makaha International Surf competition. Even with all of the accolades, our impact in women’s surfing was brushed off as a recreational, social sport rather than serious athletic competitions, forgotten in surf history. As pioneers in the sport, this book provides insight into the development of women surfing as it progressed through our lives. Fast forward to 2020, where for the first time in history, women’s (and men’s) surfing will be a recognized sport in the Tokyo Olympics.

Maya Angelou hit it on the head with her quote, “There is no greater agony than keeping an untold story inside of you.”

Leave A Comment