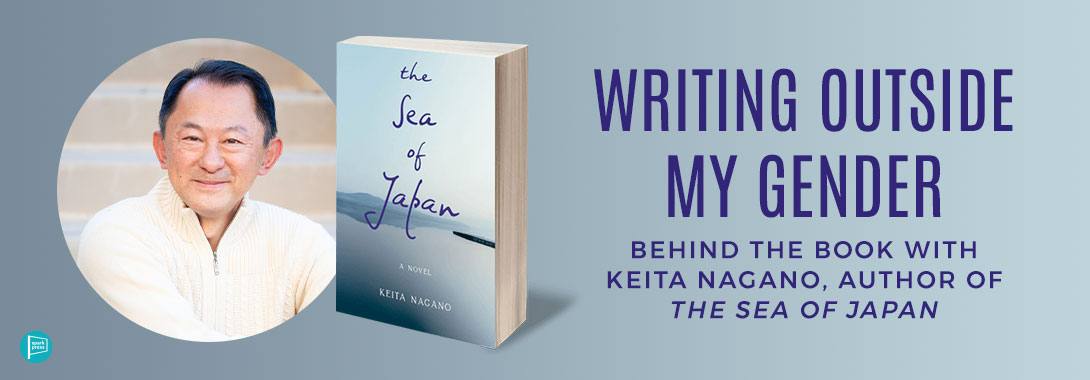

People ask me why I chose a female main character—the opposite of my gender. That’s a great question, especially since this novel is in a first person point-of-view. My voice is my main character’s voice: Lindsey Thatcher, born and raised in Boston.

Let me be honest. As a debut author in the American publishing industry, I looked hard at the probability of sales. This was the entrance, and if I neglected to pay adequate attention, I could not go beyond the entrance. Even though I’ve published more than 20 books in Japan, this simply doesn’t count in the American market. In American fiction, 80% of the readers are female, and therefore a female protagonist is well-appreciated.

Good strategy, isn’t it? Sure enough, if we write professionally, we want to sell our book. We’re always interested in a better probability. At the end of the day, the industry gauges the success by a book’s merit and the number of sales.

However, I shall also be honest with the more fundamental issue of why I wrote from a woman’s point-of-view. Creating the main protagonist’s characteristics and personality has a direct correlation with “why authors write.” A mere marketing strategy excites the author only so much, so passion has to come first to the author, and then strategy may or may not follow. To me, this order is the golden rule, and it shouldn’t be compromised. Because I am a debut novelist here, I would have chosen a different story if I had not seen good strategies in the plot. But still, my passion had to come first. Perhaps I’m enough of a veteran in writing to acutely know that the audience sees through everything authors try to plant.

In The Sea of Japan, I chose Lindsey because my main character had to be a fisherwoman, not a fisherman. When Lindsey proceeded to the fishery world in the Toyama Bay, she said, “I was proud to be the first American fisherwoman in Japan. The fact that there was no word, fisherwoman, in the English dictionary made me even prouder.” I wanted to write a character who was a pioneer in their world.

Besides gender, authors also have to choose the protagonist’s age, race, educational background, marital status, hobby, family situation, etc. It’s great if your choices happen to fall right on one of the cultural “trends” of the moment, or if they echo recent mega-hits from platforms like Netflix or Amazon Prime Video. Still, I would never advise authors to take a character from one of these shows and reverse engineer them. Again—readers see through every calculation you make, and your voice would sound more commercial and less passionate because of the calculation.

Needless to say, a male author writing a female voice is a big risk. In the Japanese language, along with some other Asian languages, conversation style in fiction may slightly differ from one gender to another. Thus, there’s a big chance that the readers may feel the “artificialness” in the tone of the voice. In my published books in Japan, I have many female characters, but I always found it difficult to make them sound real in their gender. For example, in the Japanese language, if you add certain words like “wa” or “wayo” at the end of the text, it would signal womanly talk. My best possible metaphor of this is Californians mimicking a deep South accent. It may come close, but southerners may still find it artificial. The English language has fewer differences in the language gender gap, but I still believe the readers’ expectation demand that authors write cognitively differently.

Often, readers know an author’s gender prior to reading their books. If an author isn’t careful to flesh out the character realistically, they run the risk of pulling the reader out of the story by relying too heavily on stereotypes. For example, a female protagonist might pay more attention to traditionally feminine interests, like flowers or fashion, than a male protagonist. I didn’t want Lindsey to talk about feminine details like flowers and clothes, just because she’s a female character. That would not help the reader understand who Lindsey is. That’s not to say that she never talks about such things. If they occur naturally, or are important to the story, that’s when she may wax poetic about a cannoli. The bottom line is you need to give the protagonist life, no matter who they are. It was more important to write about how Lindsey felt about a red rose than bringing up ten different types of colorful flowers in the story.

One more thing. If your reason for bringing in these preferences is only because of “gender make-up,” this will also kill your story. Here is an example: so yes, Lindsey loves sweets. She particularly loves the sweets at Mike’s Pastry in Boston. Lindsey says to her fishing partner, Ichiro, when she’s taking him for a tour of her hometown, “Oh, you have to see me lining up for cannolis at Mike’s Pastry. There, yes I will shine like a dazzling summer sun!” Yet, if this cannoli was only presented for the author’s effort to make Lindsey look like female Lindsey, the readers will get bored. There must be another reason to bring cannolis into the story. In The Sea of Japan, the cannoli is the main tool to connect Lindsey and her grandfather, who is the best fisherman in America and plays an important role later in the book.

If the novel is driven by a deep voice, the author shall do their best to be attentive to every preference of the character, regardless. As such, a male author’s effort in writing a female main character is difficult—but not more difficult than being aware during the writing process of the preference of all your characters.

That is why, before I wrote this story, I became a disciple of a Tokyo veteran die-hard sushi master for a couple of months. That is why I rode on the actual fishing boats often in several fishery methods. Knowledge collection can be done by the internet these days, but making yourself the sushi master or fisherman can only be done if you try it yourself and feel what it is like.

It’s an issue of paying attention until the character truly becomes yours. As one of my writing masters, one of the most prominent and famous Japanese authors, Noboru Tsujihara, said in his lecture, “Authors should be naturally bisexual anytime when needed.”

Leave A Comment