On January 3, 2014, my beloved youngest daughter, Giana Natali, died of a heroin overdose. She was 33, a veterinary nurse, and had suffered since adolescence from major depressive disorder, anxiety, and anorexia. After seven years of only moderate symptoms, in her late twenties, her depression and anxiety began to worsen and were complicated by several incidents where she used opioids to relieve physical pain. At least initially, the opioids also relieved her depression and anxiety. In time she became more dependent and her depression worsened.

In the twenty months before her death, she admitted herself to six residential rehab facilities and attended several outpatient programs. As we were very close, I was intimately involved with her struggle to get well. Although I was very worried about her, I didn’t think she would die. I was stunned when the worst happened.

Grief

For almost two years after Giana died, my primary goal was to survive and eventually regain some equilibrium. Although I journaled, sometimes writing entries directly to her, my grief at that point was best addressed with distractions. I couldn’t sustain a writing practice for any length of time.

But I continued to be besieged by feelings that we had not done enough for her, not asked enough questions, not made good decisions. I was plagued with “what ifs”, so common when families suffer this kind of loss. To address those doubts, I began reading bins full of letters, journals, and treatment materials that Giana had left behind in a storage unit. I kept a notebook with responses to what I was reading.

However, instead of quelling my doubts, they grew as I tried to understand more by doing research into opioid use disorder, treatment, and policy. I came to the conclusion that Giana’s treatment was not aligned with the most recent research and evidence-based treatment practices. I discussed what I was discovering with Giana’s father Lou, who is a lawyer, and other members of my family. We realized that we could read all of Giana’s medical records and treatment notes by establishing her estate and requesting them. Over the course of the next year, I must have read the records twenty times, organizing them by timeline, treatment modality, cross-referencing with research, and writing in my notebook about my concerns. I was very angry and wanted to act.

Writing her story

My family considered a lawsuit, but in the end, we decided against it. A lawsuit of this type drives to a financial settlement, and this was not about money. This was about what happened to Giana, and how we might prevent other families from suffering a loss like ours. I decided that in these circumstances, the pen was mightiest. I began writing Giana’s story.

When I shared the first draft with my writing group, they felt that while the book provided important information for impacted families and the general public. However, it was lacking the personal story of my relationship with my daughter and the processing of my grief. I had, of course, largely avoided this because it was so painful to write. But I pushed forward, with a lot of tissues, and taking a day off from time to time when I just couldn’t face the page.

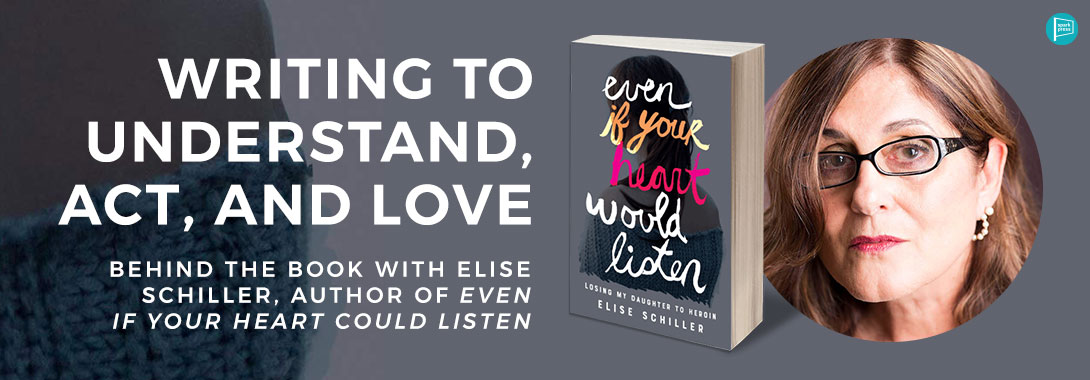

Apparently, I succeeded in weaving the personal story with the information I wanted to impart, because the second draft was very well received by my readers. After more revisions, the book, Even If Your Heart Would Listen, was completed in early 2018, and was accepted for publication by SparkPress. With publication day looming, I have been doing more speaking, writing, and advocacy work. I feel that one of my purposes in taking up the pen is being fulfilled.

Closure

But what about the grief, what about closure? The grief has softened, to be sure. But no amount of writing or advocacy will erase the deep loss that I feel every single day. In the Afterword of the book, I write: “People have asked me if writing it has been cathartic. If that means I have ‘purged’ my strong feelings, then no. All of my feelings related to her—love, sorrow, pride, regret, anger, admiration—that soup of boiling emotions—remain intact. But if not catharsis, at least satisfaction. I have told truths about her and her story that I needed to tell. There will be more to say, in other ways, because she is always with me.”

I have had another, unexpected experience from writing my book. When a loved one dies abruptly, there is a pervasive feeling of disbelief. How could someone you were texting with just hours before be gone? How could it be that you will never touch that person, talk and laugh with them, share the experiences large and small that make up a continuing relationship? Over time that feeling of disbelief turns to crushing sorrow. Yet as I spent day after day reading and writing, I felt that my relationship with Giana was being extended, even growing. Although much of what I read was distressing, still I found my understanding and love for my daughter growing even greater.

There are still bins of clothing, CDs, high school and college papers, and memorabilia of all kinds in that storage unit. And I’ll go through it very slowly, perhaps writing some more memoir along the way.

Leave A Comment