What does “kill your darlings” really mean?

One of the most famous pieces of writing advice is William Faulkner’s, “In writing, you must kill all your darlings.” Though creative processes are highly subjective, this is one of the core pieces of editing advice that everyone seems to agree on.

To kill one’s darlings is to cut out elements of your manuscript that you love which may not be working for your book as a whole. This isn’t always easy, since, as writers, we can get a little blinded by our work. When you’ve spent so long on a project, it’s easy to point to part of it and say it’s essential, when in reality, the manuscript might be stronger without it.

Examples of “darlings”

Examples of “darlings”

The darling you kill doesn’t have to be so literal—you don’t need to go through your manuscript and kill off every character that you like (though many writers go that route). Here are a few more darlings that you can look into murdering:

Purple prose

Everyone likes description—it’s part of what helps us readers slip into a story. But when the prose becomes too flowery, and the “rainy day” becomes “a day plagued by the hazardous, smattering drops of rain, so persistent in their dreary descension that one might think that the great god Zeus was crying vengeful tears”—that might be a darling you have to kill.

Your favorite scene

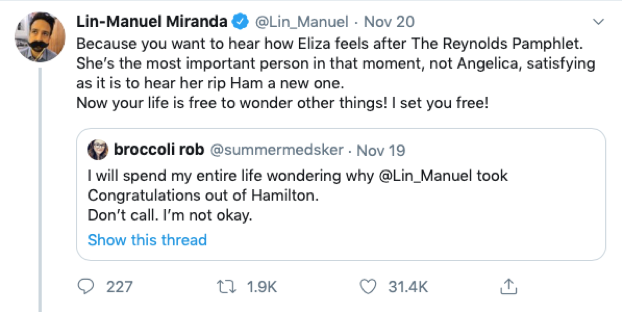

In the musical Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda cut the song “Congratulations,” from the Broadway show. Though some fans were sad to see Angelica’s angry reaction to the Reynolds Pamphlet cut, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s response shows that great things have to be given up for the betterment of the work as a whole.

Lengthy exposition

One of the hardest balances to maintain when writing is between dialogue and exposition. Background is great, but ten pages of it at a time is hardly palatable. Some details need to be cut. Most would argue that Victor Hugo’s deep-dive exposition of the Paris sewer system in Les Misérables is a darling that should have been killed. Interesting information? Sure, but readers no doubt care more about Valjean’s redemption arc than the details of the 360 miles of sewer.

Any idea you’re protective of

A darling is any idea that you are unreasonably protective of. This isn’t to say that every great idea you have needs to be killed—but these are the ideas that you need to take the most care with. We tend to be less likely to listen to critique when we truly love what’s under scrutiny, but of course, that is the critique we should listen to the most.

How do you do it?

How do you do it?

Killing your darlings might seem easy in theory, but when cutting time rolls around, you might find yourself struggling. So how do you go about doing the deed?

Be objective

You have to look at the big picture. Obviously, you want to write something you love, but being objective means that you look at what will improve the work as a whole. Your darlings aren’t always going to be quantitatively poor writing—in fact, they might be some of your best. But just because something is well-written, doesn’t mean it works.

Ask others to help you

Being objective is easier said than done, especially when you’ve been neck-deep in a project for months. So when you’re struggling on how to polish your manuscript, ask for help. Beta readers can identify the darlings that you’re struggling to find.

Drop the ego

You might not want to believe it, but sometimes what stops us from killing our darlings is our own ego. In his memoir, On Writing, Stephen King wrote, “[K]ill your darlings, kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.” Think about what’s best for your work, not what’s best for you.

Visiting the graves

Visiting the graves

Killing your darlings doesn’t mean they have to be gone forever. When you cut something from your manuscript, paste it into a separate document. Not only will this ease the pain of killing your darlings, but you can revisit these little gems whenever you miss them.

Leave A Comment